Ruth Enid Zambrana Named Distinguished University Professor

July 09, 2020

Zambrana is a renowned and pioneering interdisciplinary scholar and mentor.

By Jessica Weiss ’05

Ruth Enid Zambrana, professor in the The Harriet Tubman Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, was named 2019–20 Distinguished University Professor, the highest academic honor bestowed on tenured faculty by the university. The title is a recognition not only of excellence, but also impact and contribution to the faculty’s field.

Zambrana’s scholarship applies a critical intersectional lens to structural inequality and racial, ethnic and gender disparities. She has published extensively on issues related to public health and social inequality, educational pathways and equity, and underrepresented minority faculty in higher education. Zambrana has also mentored over 50 scholars in various fields of public health, medicine and the social sciences.

In addition to chairing the department, she is affiliated with the African American Studies Department, the Department of Sociology, the School of Public Health, the Department of Community and Behavioral Science, the Maryland Population Research Center, the U.S. Latina/o Studies Program, the Latin American Studies Center and is the director of the Consortium on Race, Gender and Ethnicity. She is an adjunct professor of family medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, School of Medicine.

“I am very humbled and very honored,” Zambrana said. “I have dedicated my life to equity because everyone deserves opportunities. I hope this distinction allows me to make my work even more impactful.”

Zambrana began to observe structural inequality early in her life. She grew up in Jamaica, Queens, a diverse, working class enclave in New York City, where she had friends and neighbors from a range of backgrounds. The daughter of Puerto Ricans whose first language was Spanish, she helped her parents navigate the language barrier—in banks, within the healthcare system and at the candy store and drugstore. They were often treated with disdain and disrespect, which Zambrana says was “very jarring but very instructive.”

In spite of that discrimination, Zambrana’s mother instilled in her the importance of fighting for justice and respecting difference. By her third year of undergraduate studies at Queens College, the civil rights movement was in full swing and Zambrana joined the protests for equality.

In college and later in graduate school she discovered a love for research in a variety of disciplines, including psychology, sociology and education—always focused on structural inequity. While pursuing a Master in Social Work and Social Policy at the University of Pennsylvania, she conducted research in low-income schools in Philadelphia and was struck by the unequal and poor quality treatment of the children she observed. She sought to use knowledge not just as a tool of empiricism but also of social justice, translating and applying findings for the greater good and reversing dominant culture thinking about individual or cultural responsibility for failure. She credits a number of faculty mentors for encouraging her scholarship along the way, even when it was seen as unconventional.

“It was evident to me that the whole story was not being told or understood,” she said. “The narrative was wrapped around the myths of pulling yourself up by your bootstraps and meritocracy, with class and race omissions, blindness and silences. It felt hurtful, incomplete and oppressive in the erasures of entire groups of people.”

In the early 70s, while working as an admissions counselor at City College, New York, seeking to help disadvantaged students succeed, she had a realization. Many of the students she saw—predominantly young African American and Puerto Rican students, as well as low income white students—were on public assistance, working several jobs or in small family businesses. But the professors often judged such students to be unworthy of opportunity.

“It became clear to me that I needed to be on the other side as professor and also as a knowledge producer of inequity in both health and education,” she said.

Zambrana applied for a doctorate in sociology at Boston University and earned a full scholarship for four years. She continued to work in minority communities in New York, Philadelphia and Boston, researching aspects of structural inequality, racism and elitism through qualitative and mixed (quantitative and qualitative) methods. At the time, the concept of “intersectionality” still wasn’t being discussed in academia.

“Color, race, ethnicity, class—I could see right off the bat they intersected,” she said. “Intersectionality was my frame without the word because it was all about power relations; all about the stereotype of low income people as non-thinkers.”

In the late 70s, she was finally able to put a framework around her research when she received an invitation to join a group of women of color professors of sociology, all of whom had seriously thought about issues of race, ethnicity, class and gender. Among them was Bonnie Thornton Dill, now the dean of the UMD College of Arts and Humanities and a fellow professor of women’s studies. The group spent five years conducting research and giving courses, as well as sharing their personal stories experiencing race, ethnicity, gender and class from childhood to adulthood.

“I learned the roots of Ruth's fighting spirit, her strong commitment to social justice and developed a deep appreciation for her strength and determination to overcome and excel in the face of obstacles that sought to diminish her excellence because of her ethnicity, accent and gender,” Thornton Dill said. “It has been a privilege to work with her and watch her live out those values over the years.”

Since then, Zambrana has conducted pioneering scholarship that applies a critical intersectional lens to structural inequality. She has over 150 peer-reviewed articles, book chapters, reports, and monographs, including articles in several high-impact journals. After appointments at the University of California Los Angeles, George Mason University and more, she joined the University of Maryland in 1999.

With Thornton Dill, she was a co-founder of UMD’s Consortium on Race, Gender and Ethnicity, whose mission is to promote intersectional scholarship that examines dimensions of inequality through the lived experiences of historically underrepresented minorities, as well as to provide support and mentoring. Zambrana has served as the consortium’s director since 2006.

Her latest book is “Toxic Ivory Towers: The Consequences of Work Stress on the Health of Underrepresented Minority Faculty” (2018), which captures not only how various dimensions of identity inequality are expressed in higher education and how social statuses influence faculty health and wellbeing, but also how policies and practices can transform institutional culture.

Roberto Patricio Korzeniewicz, the chair of the Department of Sociology, said Zambrana has effectively “broadened the discourse” on structural inequalities, race, ethnicity, gender and socioeconomic status in public health over the past three decades.

“Her contributions to the social and health sciences ... have been instrumental in shaping a paradigmatic shift from individual/cultural centered perspectives on racial and ethnic health disparities over the life course to a social determinants approach,” he said.

Zambrana is also a committed mentor and has worked in that capacity at institutions including the University of Puerto Rico’s School of Medicine, the University of Illinois at Chicago, the Midwest Latino Health Research, Training & Policy Center and the American Association of Medical Colleges. She is especially committed to working with underrepresented minority faculty, many who come from low-income and working class backgrounds, like she did.

Zambrana said she plans to continue to mentor and support minority faculty for as long as she can. “We need to help faculty open that door of opportunity,” she said. “Humanity, equality and respect are the basic values of a society. The academy has to set an example.”

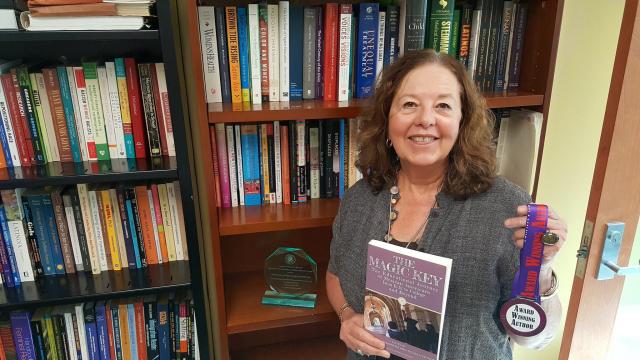

Image info (top to bottom): Zambrana was a co-editor, with Sylvia Hurtado, of "The Magic Key" (2015), which provided an empirical study of the school experiences of Mexican Americans.

Zambrana (far left) with the week-long Intersectional Qualitative Research Methods Institute (IQRMI) 2018 cohort. The institute focuses on qualitative research methods at the intersection of race, gender, class, ethnicity and other dimensions of inequality.